Our mission here at Building Ventures is to help create a better built world. But what does a better built world look like? What are the essential elements or defining processes? Most importantly, what must we do now to create this better future? In this series, we explore how we must change the way we design, build, operate and experience the built environment to realize an improved future for us all.

At Building Ventures, we believe that a better built world is one that enables people to meet all of their needs. After all, if there were no people on this planet we wouldn’t need buildings. We constructed our built world to meet our most basic needs—including shelter from increasingly inclement weather conditions as well as our physiological safety and wellbeing. Now, our building stock is aging and our technological capabilities are improving rapidly. We have an opportunity at this inflection point to invest in a better built world that satisfies all of our needs, even and especially those at the top rungs of Maslow’s hierarchy.

As investors, we look to solve the problems we face today while working to create a better future. Because of this dual-sided goal, our mandate is to understand the urgent, critical jobs to be done and simultaneously envision the future we want to help accelerate. This dual focus on the built environment is familiar for me—in fact, it’s defined my professional career even before joining the team here at Building Ventures.

My path to Building Ventures includes a decade dedicated to achieving the promise of cities. After undergrad, I began my career in economic policy, contributing ideas and proposals to make cities better for all. Following that, I worked in local economic development to create the conditions for people to thrive. And in venture capital, in a similar respect we work to outfit the companies we back with the right resources and relationships that can allow them to ride the tailwinds of markets and policy and contribute their solutions to a better built world.

When it comes to the future, our built world needs to be better for all people. We must position all the critical elements of the puzzle, from technology to public policy, in order to create affordable, accessible spaces that enable wellbeing where we live and work

Our built environment shapes our health and wellbeing

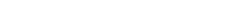

When we talk about wellbeing, it’s easy to mistake the component pieces as “nice to have” and not fundamental needs, especially when these pieces are non-medical. According to the Center for Disease Control, the social determinants of health, or non-medical factors that shape our physical and mental wellbeing, include health care and quality, education access and quality, economic stability, social and community context, and neighborhood and built environment. Our buildings—as well as our infrastructure and our cities—are one of five key factors that impacts our health.

And this impact on our health is significant. For example, a person’s neighborhood and built environment directly contributes to your lifespan. Pollution from the chimneys and exhausts of our built environment, contaminated water from lead pipes, and housing that lacks light, fresh air, and green space all contribute directly to the length of one’s life. Here in Boston, the data shows a sharp difference between two neighborhoods separated by two miles: “There is about a 23-year difference in life expectancy between part of Back Bay, where life expectancy is 91.6 years, and part of Roxbury, where life expectancy is 68.8 years, according to a 2023 Boston Public Health Commission report.”

Image via Center for Disease Control

If we know the built environment is a central component of our health and wellbeing, what can we do about it? How can we invest in a better built world that leads to greater and more widespread wellbeing? Since our built environment today is one of our leading causes of pollution, can it also be our path to cleaner air? If our built environment is the problem, can it also be the solution? It’s this final question that motivates me and the rest of the Building Ventures team.

When you think of those two neighborhoods in Boston with different life expectancies, one of the invisible differences between them is the air quality. Air quality in Roxbury is not only worse than Back Bay; it’s also significantly worse than in other areas of Massachusetts. One way to mitigate this is to green residential homes and industrial buildings in the area. To accelerate that change, we connected our portfolio company Elephant Energy with a Boston-based community development financial institution doing work in Roxbury to explore how they can work to electrify and green residential homes where air quality most needs to be improved.

The other less obvious way to drive greater wellbeing in the built environment is through investments in our core civil infrastructure. In cities like Jackson, Mississippi, and Flint, Michigan, poor water quality threatens the wellbeing of residents, and new construction tech is seeking a solution. These startups are offering AI-enabled predictive modeling to help local governments identify which pipes are likely to contain lead and should be dug up, examined, and replaced. By leveraging this technology, municipalities save money and time on projects that directly improve the water quality for residents—in turn, improving their wellbeing.

In addition to residential electrification and infrastructure, commercial solutions can make the buildings where we work better. For many of us, this is where we spend most of our day. And portfolio companies of ours like Work & Mother make sure the workplace is built to serve all of us. Most of our existing commercial buildings were not designed with nursing mothers in mind. But the recent PUMP Act requires accommodations for parents, and these working parents aren’t a small exception. In 2023, 63% of women with children under three participated in the US workforce. As Work & Mother Founder Abby Donnel points out in a recent article in Fast Company, “A suite isn’t just a perk. It’s a way for employers to retain workers.” Employee retention strategies are especially important today, when professional and business services have the highest percentage of unfilled jobs across industries and workers have more power than ever in deciding where they want to work.

Work & Mother suites like this one ensure our buildings and our workplaces are designed for nursing mothers.

And in addition to improving our commercial spaces today, we can also begin to plan for how to adapt them in the future. Our portfolio company Adaptis uses a proprietary simulation engine to run thousands, sometimes millions, of scenarios to determine the most environmentally friendly and profitable way to retrofit or build a commercial or residential building. The Adaptis platform guides capital planning decisions for asset managers and design decisions for architects that help us prepare for climate adaptation and maintain our safety and security where we live and work.

At Building Ventures, we have the unique vantage point of seeing startups everyday that are using technology to address issues with our built environment, including improving air quality, water quality, and our health at work. We are on our way to creating a built world that shapes our health for the better, and with recent policy changes, we find our industry and our cities at an inflection point.

Designing our cities for better wellbeing

In driving for these outcomes and a better built world for the people in it, technology plays a key role, but so does our public sector. In the US, our last major urban planning exercise may have been The New Deal, which was first enacted more than 90 years ago. Today, we have a similar opportunity to develop a better built world with the passing of the Infrastructure Reinvestment Act.

The New Deal led to the creation of the FHA, which spurred a movement of single-family home-building in largely segregated suburban neighborhoods throughout the US. And homebuilders like Levitt & Sons rode this tailwind by launching some of the first examples of mass produced housing to produce affordable homes. This led to a large expansion of home building, which eventually led to pushback from residents of neighborhoods and restrictive building codes that limited population density and new expansion. As Brian Potter explains in Construction Physics:

“In a 1969 survey from the National Association of Home Builders, just 3% of homebuilders mentioned building codes or zoning as their most significant problem. But by 1976, that had risen to 38%, by far the most severe problem listed by builders.”

Since Levittowns first showcased prefab homes with a manufacturing line production process, the US has largely abandoned this style of homebuilding, while other countries like Sweden and Japan have taken the idea and perfected it. This is due, in large part, to the differences in our building codes:

“Building codes in the US try to make buildings safe by prescribing exactly what materials must be used and how (prescriptive code). In Sweden, the government does this by setting goals and letting builders come up with a way to achieve them (a performance code).”

Both prescriptive and performance code result in structural soundness and safety, but only in the US does each residential building need to be granted a permit. In the US, before work can begin the contractor must be granted a permit and during construction their work is often halted as inspectors make periodic inspections.

One day, we might have a system more like Sweden’s or a streamlined offsite inspection process as construction shifts to incorporate more modularity. But until then, for the practitioners in the industry today we have solutions like our portfolio company UpCodes, a comprehensive compliance and product research platform to help builders accelerate their time to completion.

The New Deal, which led to the FHA and its redlining, failed at creating a better built world for all. But now, with the largest infrastructure spending bill in history, and similar momentum at the local level, we have our next opportunity to seed a better built world for all. The IRA’s $27B Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund has already driven adoption of residential electrification beyond initial expectations. And here in Massachusetts, the largest housing bill in the state’s history recently passed to ensure housing is affordable, sustainable, and available for all. The $5 billion spending package in MA includes more than 4x the previous amount authorized for sustainable and green housing initiatives, so programs like Mass Saves can make it easier for all residents to decarbonize their homes. Additionally, it rethinks how our building stock is allocated in our cities with tax credits for commercial property conversion to residential. We view this conducive regulatory environment and Fed Chair Powell’s recent call for rate cuts, as a unique opportunity much like The New Deal presented over 90 years ago.

Ensuring everyone has access

As we make these investments in our built environment, people will naturally flock to live in these areas. Our built environment needs to be able to accommodate the demand. In order to do that, our housing stock must be affordable.

In this upcoming election, republicans and democrats, Gen-Z and earlier generations, all rank housing affordability as one of the top issues determining their vote in this presidential election. A more efficient home construction process and solving the labor shortage we have in the construction industry are two ways to bring down the costs of real estate.

As Mayra points out in her recent article on leveraging AI for better building, tech needs to make the process of building easier and better for the people doing it. And companies in our portfolio like Mosaic are showing what that path can look like.

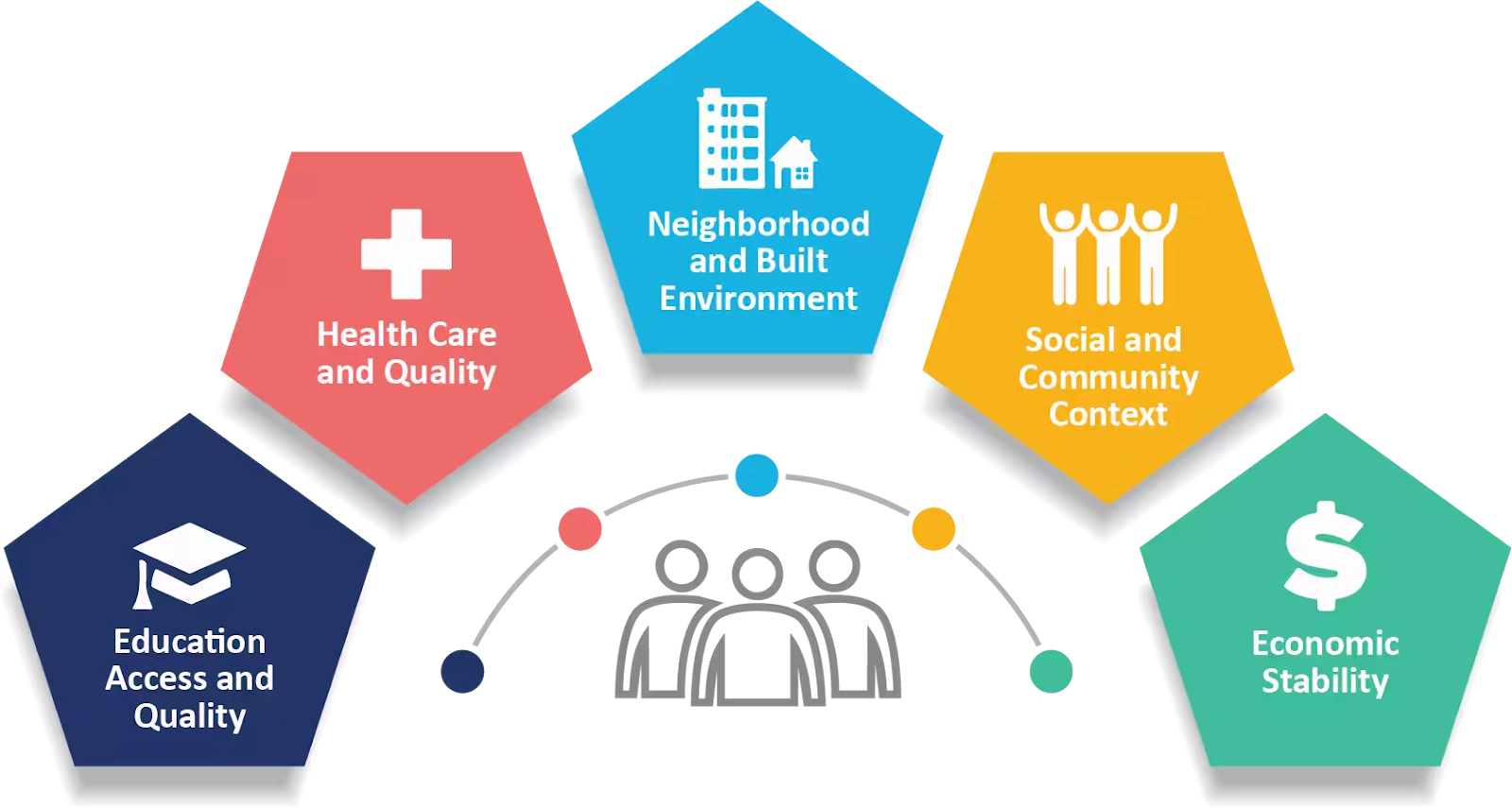

Mosaic uses its software to read building plans and create guides for each worker on site. This allows workers to work faster and technology to speed up the management of project planning, purchasing, supply chain, and quality control.

Mosaic construction site and the Mosaic programming software via Business Insider.

The other major lever to increase housing affordability is to address the labor constraints in the construction industry. As of May 2024 there were 339,000 unfilled construction jobs. This number is up since the pandemic, and will likely increase by the end of this decade as 41% of baby boomers are expected to retire by 2031. Since many of these workers will be senior and skilled, the gap they leave behind will be felt most acutely among skilled crafts. This labor shortage has led many projects to be delayed or canceled, with Deloitte & AGC reporting that 60% of projects have been delayed or canceled due to workforce shortages.

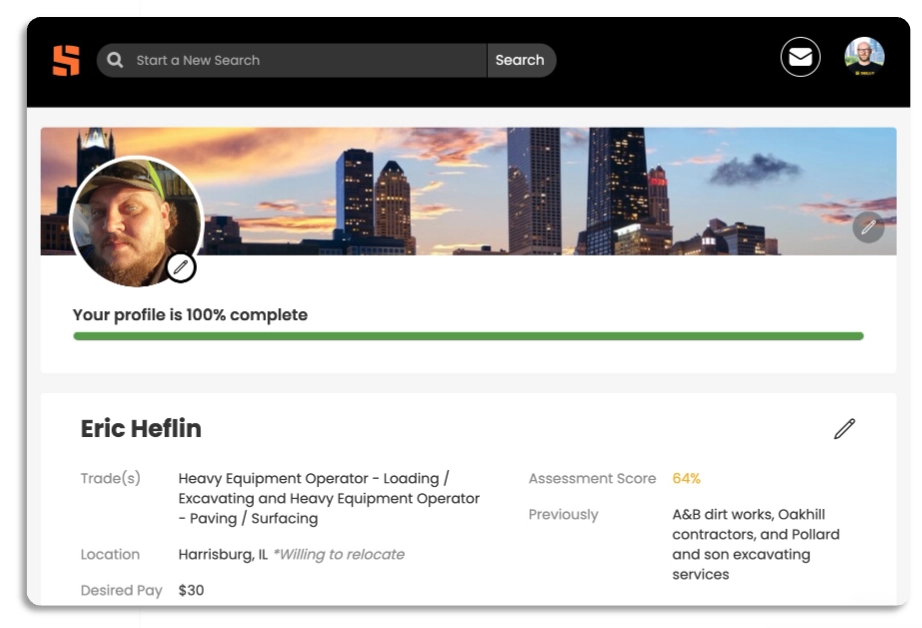

Companies like Skillit in our portfolio aim to help match skilled workers with open positions by widening the aperture of what those workers might consider as relevant job openings. General contractors who are hiring can search for workers based on the location of the project and the skills they need that worker to have and see relevant matches alongside a history of that individual’s work experience in that trade. By building the LinkedIn for deskless workers and effectively matching job openings with skills instead of titles or trades, Skillit’s mission is to solve the industry’s labor crisis.

The Skillit platform supports skills-based hiring for trades.

Envisioning a better built world

So what does a better built world look like? It must be affordable, accessible, as well as sustainable in order to improve our wellbeing. In a global summer of heat records, we know that a city’s best defenses can be greener cities with more trees, less cars, and decarbonized buildings. And when Italy, with its marble streets hit 119.8º F, maybe the model for a sustainable modern city can be found in cities like Singapore.

In Singapore, average life expectancy has increased by more than 20 years within one generation. Dave Buettner, who studies areas around the globe with high life expectancy, attributes this to the city’s move away from a car-centric design. In Singapore, personal automobiles are taxed so heavily that only 11% of people own cars. And this money is used to fund a public transit system that is clean, reliable, and locates a station within 400 yards of most residents. Leaving the 89% of Singapore’s population that does not own a car to commute on foot, breathe air with less pollution, and navigate a city with less sprawl and traffic.

But our north star isn’t any one city; it’s a better built world that positions all people to thrive. And our portfolio companies are with us on that mission to bring this improved physical environment into fruition and ensure that our buildings meet our needs at every level of Maslow’s hierarchy. Our vision isn’t utopian and distant; it’s solving today’s problem while iterating and improving to realize better and better tomorrows. And we believe the companies taking advantage of today’s policy and market dynamics to build sustainably and affordably to meet people’s needs can be the unicorns of the next decade.