Our mission here at Building Ventures is to help create a better built world. But what does a better built world look like? What are the essential elements or defining processes? Most importantly, what must we do now to create this better future? In this series, we explore how we must change the way we design, build, operate and experience the built environment to realize an improved future for us all.

Recently, I was in a meeting where I heard a builder casually proclaim that software isn’t going to bend the cost curve or materially improve how we build. As someone whose career has been focused on backing entrepreneurs with plans and products to improve how we design and build, I tensed at the comment—and it’s stuck with me since that meeting. My immediate reaction was denial, but since that day, I’ve come to accept that it is a legitimate criticism. Even with software solutions on the market, our industry is routinely battling rising costs, coordinating scheduling delays and disruptions, and navigating the hard feelings that accompany many project outcomes. That’s because we’ve come to accept over time, over budget, and overworked as part of the process of construction and to date we have lacked the tools to change this approach to projects. But that is now totally avoidable if we embrace and leverage innovation and support the solutions that will allow us to improve the construction process. When we talk about our vision for a better built world here at Building Ventures, we see the process of building becoming more dependable, sustainable, transparent, trackable, even replicable. And in our ideal future, software will both bend the cost curve and make building better.

Envisioning a better built world

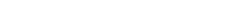

In 2016, Travis Connors and I were working on the fund that would lead to forming Building Ventures as a venture capital firm. We could already see more startups launching that targeted design and construction along with building operations. But something else was happening, as well. Katerra and WeWork were founded, funded, and gaining not only traction but attention. While the fate of these two companies was determined by their own—in some cases, self-created—challenges, they were a wake-up call for a building and real estate industry that had been exceptionally slow to change. WeWork and Katerra carried an implicit threat to the business models of construction and real estate; innovation at the heart of the business model, coupled with the technology able to support scaling, was coming. For us, this shift in business model was more important than either of these companies, or their fame or funding. Travis and I were asking ourselves this: What conditions existed that enabled their birth in the first place? What impact would these companies leave behind for a new generation of businesses targeting our built world?

At the time, I was rambling about new achievements in technology, particularly the cloud, the growing pressure of climate change, and the increasing global population. I believed the confluence of these new technological capabilities, the impending climate disaster, and the need to house more humans than ever before would incite a period of innovation. I wasn’t wrong—there has been a significant uptick in built environment innovation over the last decade. But in order for these tools to transform the way we build, we will need to shift our approach to technology in the construction industry.

Improving projects with stakeholder collaboration

At Building Ventures, we view the design, build, operate, and experience phases not as discrete stages but as interconnected and overlapping parts of a building’s life cycle. In the best cases, improving one of these phases will improve the others. Allen Preger wrote about our vision for data-driven design, and this is a key input for improving construction. And while BIM may have missed its prodigious early claims, it can be improved with a commitment to data sharing. Imagine, for instance, a world in which builders don’t have to rebuild the architect’s models. With data capture and sharing starting in design and flowing into build, the models can be developed for constructability from the jump. And instead of spending time revising models, in this world using next-generation building tools, we can devote attention and time to product selection, including more consideration for sustainability. Collaboration and discussion between stakeholders earlier in the process results in better outcomes not only for the builders and architects, but also for the owners, operators, and financiers.

With these better outcomes for all stakeholders, it’s no wonder that design-build is on the rise as the preferred method of integrated project delivery in the U.S. In order to meet the demands for integrated delivery, though, we need two things. First, we need data. Second, and perhaps more importantly, we need trust. Historically, major players in our industry are hesitant to share too much information, and this allows little chance of fostering an open, trusting relationship between stakeholders. However, if we can achieve the transparency enabled by technology, stakeholders will be able to trust and verify. And this may bring the industry the closest it will get to vertical integration.

Data is the key to trust and moving towards this integrated delivery, and many startups are currently working on solutions that will share project data. Cloud computing has enabled new collaboration platforms like Join.build to emerge and thrive. Join.build provides an environment for stakeholders across the construction process to engage and make joint decisions earlier and capture a log of all the discussions and decisions. Change orders are no longer the most feared item in the construction process since they can now be captured and communicated by systems like Clearstory to help all parties know the real story on every project. And with scheduling project controls and analytics like those with SmartPM all parties can now crisply understand the true status of the project and even how it can get back on track. All of those are possible by the use of data shared through cloud computing and super powered by growing insights using new abilities leveraging AI. As the industry adopts solutions like these more widely, we’ll begin to see a more integrated, connected approach to construction—complete with tools that provide the visibility to keep projects on time and on budget.

Construction’s hyperlocal challenge

Even as construction and design become more closely connected, these phases maintain their own unique challenges. The remit of the world’s construction entities is the literal delivery of this improved built environment. While architects and engineers design our buildings and infrastructure, the ultimate deliverable is in the hands of the builders, who are informed of course by both the design program and capital plans of the owner operators and/or financiers. Design, for example, is a step in the process that flows more cleanly across geographic borders. This is evidenced by the fact that the leading design technology vendors are global. But that’s not the case for construction—yet. Construction is the most hyper local industry in the world, so then it is the builders that most carry that unique burden.

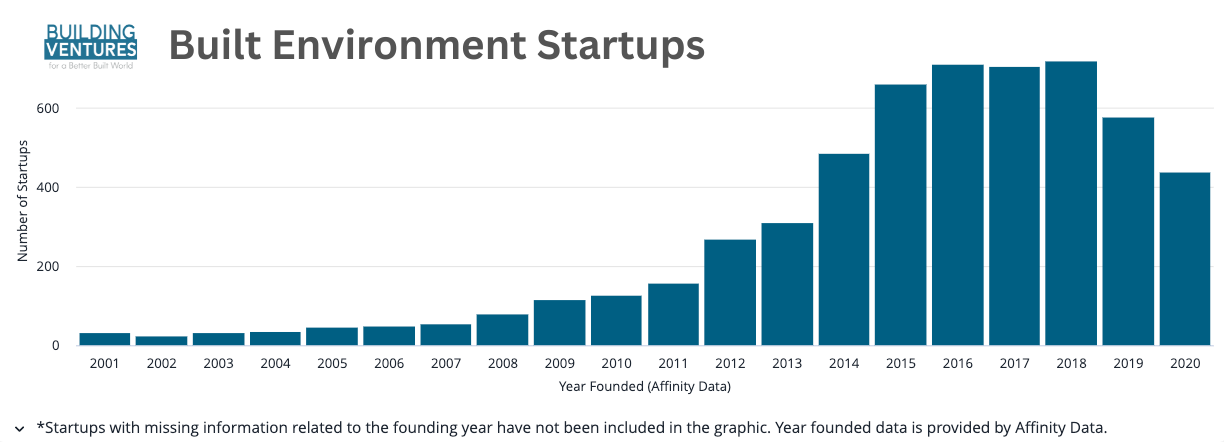

Because construction is hyper local, it is hard to replicate and scale. The weather conditions and land composition dictate materials for a project, and in many places these are chan while local codes may also mandate materials, as well as building processes, design plans, and more. Material and labor are also location-dependent, as our industry understands all too well with the labor shortages and supply chain issues during the height of the pandemic and still today. Both materials and labor also impact timelines, as they are required to move forward and complete a project. These are a lot of variables, and the challenge is greater when you take into account that these geographical differences in weather, code, labor, and materials can occur a street or two over from each other. Even within borders of a country, state, or city, the building process can look distinct.

Construction will always be this hyperlocal. But in a better built world, we will have the tools to approach each project more strategically. While early efforts in developing robotics for the job site have been challenged by the local variables in every project, we can look forward to improvements in robotics solutions. “Spot the Dog” from Boston Dynamics is the early survivor from the first round of robotics solutions that monitors job site safety, and Built Robotics’ Exosystem is installed to excavators to enable the machines to operate autonomously. Beyond these advancements in robotics, startups today are working on this with the application of AI on materials procurement, building codes, and design. In fact, our portfolio company UpCodes is leveraging AI to digitally engage building codes to inform acceptable local choices including for building products, just as Parspec is leading that charge for manufacturers and distributors on the selling side. Alongside these solutions, there’s still plenty of room to improve timely material procurement.

Construction is still uniquely challenged by a shortage of labor, a location-based problem that our industry is combatting nationwide. The Associated Builders and Contractors estimate that in 2024 alone, we will need to attract more than 500,000 new workers to the industry. That’s in addition to the year’s normal pace of hiring. In order to attract this new talent in 2024 and in the future, we need to identify those with skills that can join the construction industry. Our portfolio company Skillit does just this. Skillit provides workers with a suite of hiring tools to connect with general contractors actively looking for skilled labor. Even more, the company uses a skills-first approach to connect more talent with more GCs, which leads not only to better recruiting experiences for both sides, but also stronger employee retention—another critical component of maintaining our labor force.

Balancing local focus with mega-projects

While construction remains—and will likely always be—hyperlocal, the complexity of projects has increased rapidly, and this trend will continue. We have more mega-projects, those valued at more than $1 billion, than ever before. Data centers and other mission critical buildings for healthcare and government, including infrastructure projects, are good examples of these. It is also important to note that general contractors have historically lived off single-digit profit margins, not much more than a grocery store. Managing the increasing complexity of projects on single-digit margins is akin to flying a large body jet at 100 feet of altitude when it comes to schedule, safety, and budget. At least pilots can train with full simulation and even in bad weather can “see” where they are going. One of the early missed promises in technology for construction has been the reliable use of virtual and augmented reality to accurately track project progress. But this will come back in an improved form beyond its current documentation phase and hopefully provide accurate progress tracking and ideally even a future of holographic building where like pilots teams can digitally “see” as they build.. With the increase in demands from these mega projects and the advancement of technology, our industry will need to embrace these innovations—and likely sooner than later.

Today, we’re getting close to approaching buildings as machines with data centers. In 2024, the estimated market size for data construction in the US is $13 billion, and it’s expected to reach $19 billion by 2029. These structures have specific requirements to accommodate the number of computing machines and the amount of hardware to store, as well as the infrastructure needed to maintain the controlled environment, including the temperature, electricity, and network. Because of this, data centers are ideal candidates to maximize the application of modern methods of construction, or MMC. One advantage of this building type that provides a glimpse into the future of building is the collection of building products and components that is the heart of these facilities. This includes taking advantage of modular, pre-fab, and off-site construction approaches. Indeed, data centers are the best example of the crossover of manufacturing into construction today, which we refer to as constructuring here at Building Ventures. In that regard, data centers also are an illustration of the growing productization of construction, which has historically been project-based.

Data centers also offer a glimpse into the future of building with policy demands and owner expectations, as well, especially when it comes to sustainability. When I began in AEC, Disney was recognized as the blue chip owner/operator that would dictate their goals across the entire building lifecycle to control their outcome. Today, those blue chip owners are the hyperscale data center companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft. These tech giants are uniquely in a position to dictate sustainability goals to their builders as they strive to meet their own net-zero commitments. Increasingly, these data centers face growing local demands and policy requirements on the sustainability front as they consume more power than any building type, which has them depending on renewable power sources. That’s actually a good development, since they are the most motivated and capable when it comes to building and operating sustainably. And even better, these owners and their sensibility represent what’s to come in the future—owners, operators, and financiers that are dedicated to a sustainable building, including its construction process.

Building a better world

We are in the midst of an instructive moment that will set the tone and standard for how we build a better world. With these current tools leveraging cloud technology, AI, robotics, and MMC, we can envision a more dependable, more reliable construction process in the future. This sure feels like a tipping point. It is this confluence of factors—another strange brew—that when mixed together provides the environment to bend the curve on cost, collaboration, sustainability, and safety. Achieving this will allow our industry to deliver projects on time and on budget as a rule, not an exception.

In order to get there, we need the fuel to deliver the next generation of construction innovation to enable a better built world. Since we started Building Ventures, contech has emerged as its own category, and here at BV, we meet at least one new venture-backed company every day. However, beyond capital availability, we need to build companies that can meet the needs of a project-based industry. We are asked regularly why we chose to invest in some companies and not others; it is about the team and their commitment and ability to serve an appropriately very demanding customer base who want to deliver owner outcomes, not become tech startups themselves. One very positive development since we started BV is that most larger GCs have developed their own innovation teams to improve internal processes, and we enjoy collaborating with these teams.

It will be interesting to see if it is the architects or the builders who choose to accept more responsibility and risk in delivering owner outcomes. Both are now in a position to expand their role as they can help bend the curve and move beyond incremental improvements to embrace change and seize more of the project margin up and downstream. But this is only achievable if they leverage technology—especially the software I heard the builder write off during our meeting—to change how we build for the better.